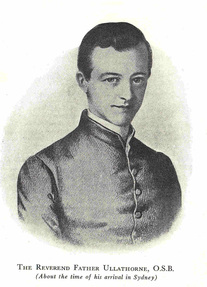

At about 8 a.m. on Monday 13th September, 1976, Fr. Fox himself heard this brief item on the ABC Radio News session: "Because of the Tridentine Latin Mass which he celebrated at East Lindfield yesterday, Fr. Patrick Fox now faces disciplinary action, but his Provincial Fr. K. Turnbull added that this disciplinary action would not go as far as excommunication" (!!). And indeed, just before beginning his Tridentine Latin Mass at East Lindfield Hall at 9 a.m. before a congregation of at least a hundred people on the previous morning Sunday 12th September, 1976, Fr. Fox had used the only escape route from his dreadful dilemma that he could then see - namely, by announcing for all to hear that this Mass (though celebrated as usual) would be a PRIVATE Mass (as opposed to the forbidden PUBLIC Mass), an announcement of course which Fr. Turnbull did not relish at all when he later heard of it, and which formed the basis of the next day’s Radio News item already quoted. But whatever disciplinary threats might now hang over him from that direction, Fr. Fox’s conscience was however clear: on Sunday 12th September, 1976 he had not celebrated the forbidden public Tridentine Latin Mass, but a self-announced private Mass, which yet however had saved his flock from being liturgically stranded and abandoned - an answer to prayer indeed!

After the aforesaid threat of disciplinary action by Fr. Turnbull against Fr. Fox as proclaimed on Monday 13th September, 1976, some Mass-Media reporters or agents rang Fr. Fox to ask what had been done to him, or what would be done to him in the way of disciplinary action; and they left phone numbers so as to learn the verdict (TV channel 9, Alan Gill - religious writer for the "Sydney Morning Herald", and "The Australian"). However, as day succeeded day in that traumatic week, on each one of which Fr. Fox was expecting to be summoned to the Provincial Office to learn the details of his disciplinary sentence, nothing of the kind happened, although Fr. Turnbull was in and out of Ashfield where Fr. Fox then lived; and on the Wednesday evening (15th September) Fr. Fox had even "sneaked in" another old Latin Mass for some of his flock in the other Sydney suburb of Killara (at the Masson family home).

But it was on Saturday 18th September, that this "disciplinary" week ended with Fr. Turnbull’s final "canonical" action therein: at 5.15 p.m. he sailed away out through Sydney Heads for a four weeks Pacific Ocean cruise as chaplain on board the cruise-ship "Fairsky" - Fr. Turnbull’s annual holiday in fact. This holiday could not have come at a better time for Fr. Fox who, still undisciplined, on the next morning 19th September, 1976 celebrated the Tridentine Latin Mass as usual for his Sunday congregation in the East Lindfield Hall - "Fairsky" so far, both on land and sea! And, interestingly, when some weeks later after his Pacific Ocean cruise Fr. Turnbull returned to Sydney, the old Latin Masses on Sundays in the East Lindfield Hall continued on unabated year after year, without any red signal from Fr. Turnbull for Fr. Fox to stop them - they might even in his mind have been private Masses, and still not public ones! Furthermore, the previous threat of disciplinary action against Fr. Fox was for practical purposes no longer mentioned - no doubt to the disappointment of the newspaper and TV reporters. But since that exciting month of September, 1976 those old Latin Masses have gone on in that East Lindfield Hall for well over twenty years, even to this day, the 9th February, 1997, when this Mass looks set to continue there well into the next century - how good God has been to us already in allowing this Mass to exist for so many years, and may His blessings be with it for the future at this oldest existing traditional Latin Mass centre in Australia!

And what powerful motivation we have for persevering with this old Latin Mass, when we learn from a French Courtoise Radio session of Jean Guitton, the great friend of Pope Paul VI, that this Pope, when promulgating the new Mass in 1969, had this intention regarding the Mass, namely, to reform the Catholic liturgy so that it would almost coincide with the Protestant liturgy, to get it as close as possible to the Protestant Lord’s supper, to tone down what was too Catholic in the Catholic Mass, and to get the Catholic Mass closer to the heretical Calvinist service (!!). 19/12/1993

We learn also that in 1986 eight out of nine Cardinals appointed by Pope John Paul II to study this matter declared that the old Latin Mass had never been suppressed, and all nine Cardinals declared that no Bishop may forbid a Catholic priest in good standing to celebrate this old Latin Mass.

Finally, "our traditionalist priests" (see above) are greatly encouraged to keep saying this Mass by these lovely words of the same Susan Claire Potts (see above): "What glory in heaven will be theirs! Imagine the look on Our Lord’s Holy Face, when He greets them in eternity! Imagine the love in Mary’s heart, when She beholds her sons. For they are the faithful ones. They are the ones obedient to the mandate of Christ. In the face of the most terrible opposition ever known to priests in the whole history of the Church, these "Latin Mass priests" have not faltered - or, if they have faltered, they have come good again - amid odd clouds in the Church’s Fairsky!

And the Lord said: "Simon, Simon, behold Satan hath desired to have you that he may sift you as wheat. But I have prayed for thee, that thy faith fail not: and thou, being once converted, confirm thy brethren." (St. Luke 22:31-32)

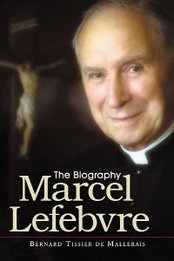

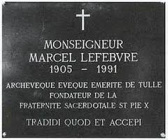

Father Patrick Fox, C.M. was called to his reward on July 24, 2007. At the age of 91, after 67½ years of priesthood, he was an exemplary model of simplicity and obedience to the seminarians and priests alike, as well as a great inspiration for traditional Catholics throughout Australia, for he had never celebrated the New Mass, and had always publicly stood firm for Tradition, Archbishop Lefebvre and the Society of Saint Pius X.