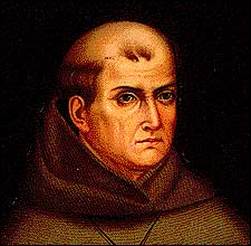

Junípero Serra, the founder of the Missions, which were the first settlements of civilized man in California, was born on the island of Majorca, part of the kingdom of Spain, on the 24th of November, 1713. At the age of sixteen, he became a Monk of the order of St. Francis, and the new name of Junípero was then substituted for his baptismal name of Miguel José. After entering the convent, he went through a collegiate course of study, and before he had received the degree of Doctor, was appointed lecturer upon philosophy. He became a noted preacher, and was frequently invited to visit the larger towns of his native island in that capacity. Junípero was thirty-six years of age when he determined to become a missionary in the New World. In 1749 he crossed the ocean in company with a number of Franciscan Monks, among them several who afterward came with him to California. He remained but a short time in the City of Mexico, and was soon sent a missionary to the Indians in the Sierra Madre, in the district now known as the State of San Luis Potosi. He spent nine years there, and then returned to the City of Mexico where he stayed for seven years, in the Convent of San Fernando.

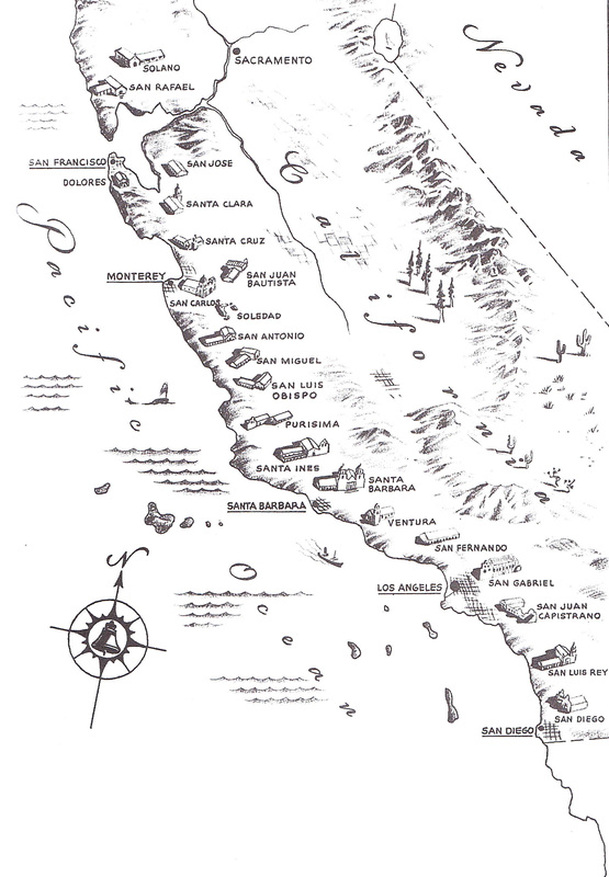

In 1767, when he was fifty-four years of age, he was appointed to the charge of the Missions to be established in Upper California. He arrived at San Diego in 1769, and, with the exception of one journey to Mexico, he spent all the remainder of his life here. He died at the Mission [San Carlos Borromeo] of Carmel, near Monterey, on the 28th of August, 1784, aged seventy- one years.

Our knowledge of his character is derived almost exclusively from his biography by Palou, who was also a native of Majorca, a brother Franciscan Monk, had been his disciple, came across the Atlantic with him, was his associate in the college of San Fernando, his companion in the expedition to California, his successor in the Presidency of the Missions of Old California, his subordinate afterward in New California, his attendant at his death-bed, and his nearest friend for forty years or more. Under the circumstances, Palou had the right to record the life of his preceptor and superior.

It was not sufficient for him to abstain from positive pleasure; he considered it his duty to inflict upon himself bitter pain. He ate little, avoided meat and wine, preferred fruit and fish, never complained of the quality of his food, nor sought to have it more savory. He often lashed himself with ropes, sometimes of wire; he was in the habit of beating himself in the breast with stones, and at times he put a burning torch to his breast. These things he did while preaching or at the close of his sermons, his purpose being, as his biographer says, “not only to punish himself but also to move his auditory to penitence for their own sins.”

We translate the following incident, which occurred during a sermon which he delivered in Mexico, the precise date and place are not given:—

“Imitating his devout San Francisco Solano, he drew out a chain, and letting his habit fall below his shoulders, after having exhorted his auditory to penance, he began to beat himself so cruelly that all the spectators were moved to tears, and one man rising up from among them, went with all haste to the pulpit and took the chain from the penitent father, came down with it to the platform of the presbiterio, and following the example of the venerable preacher, he bared himself to the waist and began to do public penance, saying with tears and sobs, ‘I am the sinner, ungrateful to God, who ought to do penance for my many sins, and not the father who is a saint.’ So cruel and pitiless were the blows, that, in the sight of all the people, he fell down, they supposing him to be dead. The last unction and sacrament were administered to him there, and soon afterward that he died. We may believe with pious faith, that this soul is enjoying the presence of God.” Serra, and his biographer, did not receive the Protestant doctrine, that there have been no miracles since the Apostolic age. They imagined that the power possessed by the chief disciples of Jesus had been inherited by the Catholic priests of their time, and they saw wonders where their contemporary clergymen, like Conyers, Middleton, and Priestly, saw nothing save natural mistakes. Palou records the following story, with unquestioning faith:-- “When he [Serra] was travelling with a party of missionaries through the province of Huasteca [in Mexico], many of the villagers did not go to hear the word of God at the first village where they stopped; but scarcely had the fathers left the place when it was visited by an epidemic, which carried away sixty villagers, all of whom, as the curate of the place wrote to the reverend father Junípero, were persons who had not gone to hear the missionaries. The rumor of the epidemic having gone abroad, the people in other villages were dissatisfied with their curates for admitting the missionaries; but when they heard that only those died who did not listen to the sermons, they became very punctual, not only the villagers, but the country people dwelling upon ranchos many leagues distant. “Their apostolic labors having been finished, they were upon their way back, and at the end of a few days’ journey, when the sun was about to set, they knew not where to spend the night, and considered it certain that they must sleep upon the plain. They were thinking about this when they saw near the road a house, whither they went and solicited lodging. They found a venerable man, with his wife and child, who received them with much kindness and attention, and gave them supper. In the morning, the Fathers thanked their hosts, and taking leave, pursued their way. After having gone a little distance they met some muleteers, who asked them where they had passed the night. When the place was described, the muleteers declared that there was no such house or ranche near the road, or within many leagues. The missionaries attributed to Divine Providence the favor of that hospitality, and believed without doubt that these hosts were Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, reflecting not only about the order and cleanness of the house (though poor), and the affectionate kindness with which they had been received, but also about the extraordinary internal consolation which their hearts had felt there.”

Serra’s religious conviction found in him a congenial mental constitution. He was even- tempered, temperate, obedient, zealous, kindly in speech, humble and quiet. His cowl covered neither greed, guile, hypocrisy, nor pride. he had no quarrels and made no enemies. He sought to be a monk, and he was one in sincerity. Probably few have approached nearer to the ideal perfection of a monkish life than he. Even those who think that he made great mistakes of judgment in regard to the nature of existence and the duties of man to society, must admire his earnest, honest and good character.