By Thomas Acres

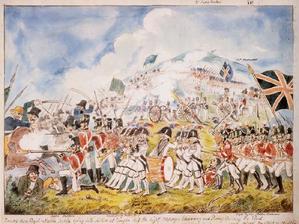

A more serious rebellion occurred in 1804, when 400 "United Irishmen" mutinied at Castle Hill, a short distance from Sydney. It started on March 4th when William Johnston, an Irishman who had been transported for his part in the rebellion of 1798 gathered together the group, armed them at Castle Hill with rifles, improvised pikes and cutlasses, and planned to raise another 300 at the Hawkesbury from where he proposed to march on Sydney and Parramatta using the catchy of liberty.

At 11:30 on Sunday night, word reached Government House that the convicts at Castle Hill were in a state of insurrection. King issued a proclamation ordering them to surrender or face court marshal, and in the early hours of Monday morning, he and a company of soldiers under Major Johnston set out for Parramatta to confront the rebels. Johnston rode on ahead accompanied by quartermaster Laycock and caught up with the insurgents at 11:30 am. at Vinegar Hill, 7 miles out of Toongabbie. They advanced within pistol shot of the rebels and called on them to surrender and take advantage of the mercy offered by the governor's proclamation. When they refused, Johnston asked to talk to their leaders, who in trusting Irish fashion, met the Englishmen Johnston and Laycock halfway. Johnston pointed his pistol at Philip Cunningham's head and Laycock pointed his at William Johnston's head. The men who had shouted for liberty offered no resistance.

In the meantime, Johnston's detachment of twenty-five soldiers had arrived on the scene. When Johnston ordered them to charge they cut the rebels to pieces. Within minutes nine lay dead, their leader, Cunningham, lay wounded, and the rest were in flight for the Hawkesbury. After Johnston caught up with them at 9 PM., retribution began. After taking the opinion of the officers about him, he directed that Cunningham be hanged on the staircase of the public store. On March 7th King announced that the principal ringleaders had given themselves up, and appealed to the rest to surrender. Only the leaders were tried, the three hundred odd of the rest were sent back to their work with a reprimand. After a brief trial eight of the leaders were hung and many others flogged, thirty-four were sent to the coal mines at Newcastle, about 100 miles north of the settlement.

During the ten years from 1808-18 the faithful of Sydney were without ministry of a priest and almost completely forgotten by the English vicars-apostolic and the Irish Bishops. Thus left without spiritual ministration the Catholic convicts were forced to attend Protestant services or else suffer twenty-five lashes for the first refusal fifty for the second, and if they persisted, the third time, they were transported to Norfolk Island, fifty miles out in the Pacific.

This period has been called the 'catacomb era' of the Church in Australia. The Faith was kept alive by laymen alone.

This long night of suppression ended with the arrival of Fr. Jeremiah O'Flynn. Jeremiah O'Flynn was born in County Kerry on December 25, 1788, he studied with the Franciscans at Killarney and entered the Trappist monastery at Lulworth, Dorsetshire, where he was ordained priest on March 9, 1813. After a period as missionary in West Indies, he became a secular priest and volunteered for New Holland, as Australia was still called. On September 9, 1815 he was appointed but Rome at the prefect of the mission to Botany Bay, or 'Bottannibe' as it was stated in the document, he was instructed to be given 'a chalice, pyx chasuble of all colours and the sum of 50 scude.' But he was refused official status from the British authorities, so he paid his own fare to the settlement hoping that his approval would follow.

Part III Part I