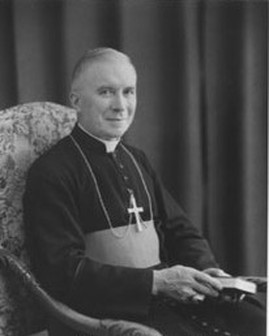

The address given by His Grace, the Most Reverend Marcel Lefebvre, Titular Archbishop of Synnada in Phrygia and Superior General of the Society of St. Pius X, on the occasion of the community celebration of his seventieth birthday, 29 November 1975, at the International Seminary of Saint Pius X, Ecône, Switzerland:

"During the course of my life, I have had many consolations, in every position given to me, from young curate at Marais-de-Lomme in the Diocese of Lille, to the Apostolic Delegation of Dakar. I used to say when I was Apostolic Delegate that, from then on, I could only go downwards, I could go no higher; it was not possible. Obviously, they could still have given me a cardinal's hat! Probably God wanted me to do something else...to prepare His ways.

And if in the course of my missionary life I had real consolations, God always spoiled me...always. He spoiled me in my parents, first of all, I must say, who suffered greatly from the war of 1914-18. My mother died from it, in fact. And my father, having helped Englishmen, especially, to escape from the zone occupied by the Germans, had his name put on the German lists, and when the last war came, his name having been carefully recorded, he was arrested and died in a German jail. Both my parents were models for me and certainly I owe much to their virtue. If five out of eight children in the family are religious priests or sisters, it is not without reason.

So I was spoiled in my parents; spoiled also in my studies at the French Seminary, in having as Superior and Director of the French Seminary the venerated Père Le Floch, who was a man of great kindness and of great doctrinal firmness, to whom I owe much for my formation as a seminarian and as a priest. They reproached me for having spoken of Père Le Floch at my consecration. It seemed to me that I could not do otherwise than to thank those who had formed me and who were, in fact, indirectly the cause of my nomination and my selection as a bishop.

But I was openly reproached with that simply because Père Le Floch was a traditionalist. I was not supposed to speak of this man, who had even been discussed by the French Parliament, because he wanted to form his seminarians in complete conformity to Tradition and to truth. He too was accused of being an 'integrist.' He was accused of involving himself in politics. He was accused of being with Action française, whereas never, in any of his spiritual conferences, had Père Le Floch spoken to us of Action française. He spoke to us only of the encyclicals of the Popes; he put us on our guard against Modernism; he explained to us all the encyclicals and especially those of Saint Pius X; and thus he formed us very firmly in doctrine. It is a curious thing - those who were on the same benches as myself, many of whom later became bishops of France, did not follow the doctrine that Père Le Floch had taught them, although it was the doctrine of the Church.

So I was spoiled during my seminary training, then spoiled even as curate at Marais-de-Lomme, where I spent only one year, but where I had such joy in taking care of a working-class parish, and where I found so much friendliness. Then I spent fifteen years in the missions in the bush, as well as at the mission seminary for six years, then again in the bush in Gabon. I became so attached to Africa that I had indeed resolved never to return to Europe. I liked it so well there and was so happy - a missionary in the midst of the Gabonese jungle - that the day I learned that they were recalling me to France to be Superior of the seminary of philosophy at Mortain, I wept, and I would indeed have disobeyed, but that time my faith was not in danger!1

I was obliged to obey and to return, and it was at Mortain, after two years as Superior of the seminary of philosophy, that I was called to be Vicar Apostolic of Dakar. I spent very happy years at Mortain. I have the best memories of the seminarians of that time and I think that they too, many of whom are still living, those who are now priests and missionaries, also have happy memories of that period. When I learned that I was named to Dakar, it was a heavy blow for me, for I knew nothing of Senegal, I knew none of the Fathers there, and I did not know the language of the country, while in Gabon, I knew the language of the country, I knew all the Fathers, and I would certainly have felt much more at home. Perhaps I would even have been capable of a better apostolate toward the missionaries and the Africans of Senegal.

I did not know that a year later yet another nomination awaited me, which was that of Apostolic Delegate. That increased the crosses a little, but at the same time the consolations, because I must say that, during the eleven years from 1948 to 1959 that I was Apostolic Delegate, God filled me with joy in visiting all those dioceses with which I had been charged by the Holy Father. I had to visit them, send reports to Rome, and prepare the nomination of bishops and Apostolic Delegates.

The dioceses confided to me at that time numbered thirty-six, and during the years that I was Apostolic Delegate they increased to sixty-four. What I mean is that it was necessary to divide the dioceses, to name bishops, to name Apostolic Delegates, and then to visit the dioceses, to settle the difficulties that might exist in those territories, and at the same time to get to know the Church. This missionary Church was represented by her bishops, who accompanied me on all the journeys that I made in their dioceses. I was received by the Fathers, and by those who were in contact with the apostolate, with the natives, with the different peoples, and with the different mentalities, from Madagascar to Morocco, because Morocco was also dependent upon the Delegation of Dakar; I travelled from Djibouti to Pointe Noire in Equatorial Africa.

All these dioceses that I had the occasion to visit made me conscious of the vitality of the Church in Africa, for this period between 1948 and 1960 was a period of extraordinary growth. Numerous were the congregations of Fathers and the congregations of Sisters that came to help us. That is why I also visited Canada at that time, and many of the countries of Europe, to attempt to draw men and women religious to the countries of Africa to aid the missionaries, and to make the missions known.

And each year I had the joy of going to Rome and approaching Pope Pius XII. For eleven years I was able to visit Pope Pius XII, whom I venerated as a saint and as a genius - a genius, humanly speaking. He always received me with extraordinary kindness, taking an interest in all the problems of Africa. That is also how I got to know very closely Pope Paul VI, who was at that time the Substitute2 of Pope Pius XII and whom I saw each time that I went to Rome before going to see the Holy Father.

So I had many consolations, and was very intimately involved, I would say, in the interests of the Church - at Rome, then in all of Africa, and even in France, because by that very fact, I had to have relations with the French government, and thus with its ministers. I was received several times at the Elysée, and several times I was obliged to defend the interests of Africa before the French government. I should also say that at that time the Apostolic Delegate, of whom I was the first in the French colonies, was always considered as a Nuncio, and thus I was always given the privileges that are given to diplomats and to ambassadors. I was always received with great courtesy, and they always facilitated my journeys in Africa.

Oh, I could well have done without the detachments of soldiers who saluted me as I descended from the airplane! But if it could facilitate the reign of God, I accepted it willingly. But the African crowds who awaited the Delegate of the Holy Father, the envoy of the Holy Father - in many regions it was the first time that they had received a delegate of the Holy Father - now that was an extraordinary joy. And the fact that the government itself manifested its respect for the representative of the Pope increased still more, I would say, the honor given to the Pope himself and to the Church. All that was, as you can imagine, a great source of joy for me, to see the Church truly honored and developing in an admirable manner.

At that time the seminaries were filling and religious congregations of African Sisters were being founded. I regret that the Senegalese Sister is not here today. She is at St-Luc, but she was unable to come. I know that she would certainly have been happy to take part in this celebration. Yes, the number of Sisters multiplied throughout Africa. All this is to show you once more how God spoiled me during my missionary life.

And then there was the Council, the work of the Council. Certainly it is there, I should say, that the suffering begins somewhat. To see this Church which was so full of promise, flourishing throughout the entire world...I should also add that, from 1962 on, I passed several months in the Diocese of Tulle, which were not useless for me because I was able to become familiar with a diocese of France and to see how the bishops of France reacted and in what environment they were.

I must say that often I was somewhat hurt to see the narrowness of mind, the pettiness of their problems, the tiny difficulties which they considered enormous problems, after returning from the missions where our problems were on a much greater scale, and where the relations between the bishops were much more cordial. In the least matters, you could sense how touchy they were; that was something which caused me pain.

And I was also surprised at the manner in which I was received into the French episcopate. For it was not I who had asked to be a bishop in France. It was Pope John XXIII at that time who obliged me to leave. I begged him to leave me free, to leave me in peace and to let me rest for a while after all those years in Africa. But he would hear nothing of it and he told me, ‘An Apostolic Delegate who returns to his country should have a diocese in his country. That is the general rule. So you should have a diocese in France, so I accepted since he imposed it upon me, and you know what restrictions were placed upon me by the bishops of France and particularly the assembly of Archbishops and Cardinals, who asked that I be excluded from the assembly of Archbishops and Cardinals, although I was an archbishop, that I should not have a big diocese, that I should be placed in a small diocese, and that this would not be considered a precedent. This is one of the things that I found very painful, for why should a confrère be received in such a way, with so many restrictions?

No doubt the reason was because I was already considered a traditionalist, even before the Council. You see, that did not begin at the Council! So in 1962 I spent some time in Tulle. I was received with great reserve; with cordiality, but they were also afraid of me. The Communist newspapers already spoke of me obviously in somewhat less than laudatory terms. And even the Catholic papers were very reserved: what is this traditionalist bishop coming to do in France? What is he going to do at Tulle? But after six months, I believe that I can say that the priests whom I had the occasion to see, to meet...I had the occasion to give Confirmation in almost all the parishes, and our relations were truly excellent. I admired the clergy of France, who were often living in poverty, but who constituted a fervent, a devoted, a zealous clergy, really very edifying.

Then I was named Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers, and there again, I had occasion to travel, this time not only to Africa, but South America, North America, and everywhere where there were Holy Ghost Fathers...the Antilles, all the English territories of Africa and all the English-speaking territories; the Belgian Congo; South Africa; and so on - all of which obviously permitted me to become more familiar with all these missions, and I really believed that God was everywhere pouring forth extraordinary graces on His Church. At that time the effects of the Council, and all this degradation, had not yet begun. So it was a very happy period, very consoling.

Then came the Council and the results of the Council, and, I must say, it was an immense pain for me to see the decline of the Church, so rapid, so profound, so universal, that it was truly inconceivable. Even though we could foresee it, and those who worked with me in the famous Coetus Internationalis Patrum (the International Group of Fathers) did foresee it, the assembly of two hundred and fifty Fathers who strove to limit the damage that could be foreseen during the Council, none of us, I think, could have foreseen the rapidity with which the disintegration of the Church would take place.

It was inconceivable, and it obliged us to admit in a few years how much the Church was affected by all the false principles of Liberalism and of Modernism, which opened the door to practically every error, to all the enemies of the Church, considering them as brothers, as people with whom we had to dialogue, as a people as friendly as ourselves, and thus to be placed on the same footing as we, in a theoretical manner, and even in practice. Not that we do not respect their persons; but as for their errors, we cannot accept them. But you have all been familiar with this portion of history for some time now.

Indeed, I suffered terribly. Imagine if I had remained with the Holy Ghost Fathers where, in theory, I should have stayed until 1974. I could have stayed until 1974 as Superior General. I had been named for twelve years in 1962. But I submitted my resignation in 1968 and, in fact, I was glad to do so, because I did not want to collaborate in the destruction of my congregation. And had I remained Bishop of Tulle, I cannot very well imagine myself at present in a diocese of France! In an environment like that, I should probably have had a nervous breakdown!

It seemed that God intended my apostolic life to end in 1968, and I foresaw nothing else than simply to go into retirement at Rome; indeed, I rented a small apartment at Rome from some Sisters in Via Monserrato, and I was very happy there. But I think that God decided that my work was not yet finished. I had to continue. Well, I could never have imagined - because there I was in a small apartment, which M. Pedroni and M. Borgeat know well - I could never have imagined at that time that God was reserving for me such profound joys and such immense consolations.

For could there be, in my last years, a consolation greater than to find myself surrounded by such faithful collaborators, faithful especially to the Church and to the ideal which we must always pursue; than to find myself surrounded by such devoted, such friendly, and such generous lay people, giving their time and their money and doing all that they can to help us? And besides them, I should recall, we must think of the tens of thousands of benefactors who are with us and who write to us - we receive their letters all the time. Now that is obviously for us and for myself an immense consolation. It is truly a family that has been created around Ecône.

And then, to have such good seminarians! I did not expect that either. I could never imagine or really believe that, in the age in which we live, in the environment in which we live, with all this degradation that the Church is undergoing, with all this disorganization, this confusion everywhere in thought, that God would still grant the grace to young men of having this desire, a profound desire, a real desire, to find an authentic priestly formation; to search for it, to leave their countries to come so far, even from Australia, even from the United States, to find such a formation; to accept a journey of twenty thousand kilometers to find a true Seminary. It is something I could never imagine. How could you expect me to imagine such a thing? I like the idea of an international Seminary and I am very happy with it, but I could never imagine that the Seminary would be what it is and that I would find young men with such good dispositions.

I believe that I can say, without flattering you and without flattering myself, that the seminary strangely resembles the French Seminary that I knew, and I believe that I can even say that it is of a quality even more pleasing to God...more spiritual, especially, and it is that which makes me very happy, because it is the character that I very much desire to give to the Seminary. It is not only an intellectual character, a speculative character - that you should be true scholars...may you be so, certainly, it is necessary - but especially that you should be saints, men filled with the grace of God, filled with the spiritual life. I believe that it is even more essential than your studies, although the studies are indispensable.

For this, then, and for all the good that you are going to do, how can you expect me not to thank God? I ask myself why God has thus heaped His graces upon me. What have I done to deserve all these graces and blessings? No doubt God wished to give me all these graces and blessings so that I could bear my cross more easily.

Because the cross is heavy, after all...heavy in the sense to which I made allusion this morning. For it is hard, after all, to hear oneself called, and to be obliged in a way to accept that people call you, disobedient. And because we cannot submit and abandon our faith. It is a very painful thing, when you love the Church, when you love obedience, when for your entire life you have loved to follow Her leaders and Her guides. It is painful to think that our relations are so difficult with those who ought to be leading us. And all that is certainly a heavy cross to bear. I think that God gives His blessings and graces in compensation, and to strengthen us in our work.

For all this, then, I thank God, first of all, and I thank all of you, and may God do as He pleases. If He wishes me to be at your service yet for some time, let it be so. Deo gratias! If on the other hand He wishes to give me a small reward somewhat sooner, more quickly, well, let it be Deo gratias also. As He wishes. I have worked only in His service and I desire to work to the end of my days in His service and in yours also. So thank you again and let us ask God to grant that this seminary may continue for His glory and for the good of souls."

1. Every Catholic, including priests and members of religious orders, must refuse to obey even the order of a lawful superior if complying with that order could endanger his faith.

2. The assistant to the Vatican Secretary of State is known as the "Substitute".

"During the course of my life, I have had many consolations, in every position given to me, from young curate at Marais-de-Lomme in the Diocese of Lille, to the Apostolic Delegation of Dakar. I used to say when I was Apostolic Delegate that, from then on, I could only go downwards, I could go no higher; it was not possible. Obviously, they could still have given me a cardinal's hat! Probably God wanted me to do something else...to prepare His ways.

And if in the course of my missionary life I had real consolations, God always spoiled me...always. He spoiled me in my parents, first of all, I must say, who suffered greatly from the war of 1914-18. My mother died from it, in fact. And my father, having helped Englishmen, especially, to escape from the zone occupied by the Germans, had his name put on the German lists, and when the last war came, his name having been carefully recorded, he was arrested and died in a German jail. Both my parents were models for me and certainly I owe much to their virtue. If five out of eight children in the family are religious priests or sisters, it is not without reason.

So I was spoiled in my parents; spoiled also in my studies at the French Seminary, in having as Superior and Director of the French Seminary the venerated Père Le Floch, who was a man of great kindness and of great doctrinal firmness, to whom I owe much for my formation as a seminarian and as a priest. They reproached me for having spoken of Père Le Floch at my consecration. It seemed to me that I could not do otherwise than to thank those who had formed me and who were, in fact, indirectly the cause of my nomination and my selection as a bishop.

But I was openly reproached with that simply because Père Le Floch was a traditionalist. I was not supposed to speak of this man, who had even been discussed by the French Parliament, because he wanted to form his seminarians in complete conformity to Tradition and to truth. He too was accused of being an 'integrist.' He was accused of involving himself in politics. He was accused of being with Action française, whereas never, in any of his spiritual conferences, had Père Le Floch spoken to us of Action française. He spoke to us only of the encyclicals of the Popes; he put us on our guard against Modernism; he explained to us all the encyclicals and especially those of Saint Pius X; and thus he formed us very firmly in doctrine. It is a curious thing - those who were on the same benches as myself, many of whom later became bishops of France, did not follow the doctrine that Père Le Floch had taught them, although it was the doctrine of the Church.

So I was spoiled during my seminary training, then spoiled even as curate at Marais-de-Lomme, where I spent only one year, but where I had such joy in taking care of a working-class parish, and where I found so much friendliness. Then I spent fifteen years in the missions in the bush, as well as at the mission seminary for six years, then again in the bush in Gabon. I became so attached to Africa that I had indeed resolved never to return to Europe. I liked it so well there and was so happy - a missionary in the midst of the Gabonese jungle - that the day I learned that they were recalling me to France to be Superior of the seminary of philosophy at Mortain, I wept, and I would indeed have disobeyed, but that time my faith was not in danger!1

I was obliged to obey and to return, and it was at Mortain, after two years as Superior of the seminary of philosophy, that I was called to be Vicar Apostolic of Dakar. I spent very happy years at Mortain. I have the best memories of the seminarians of that time and I think that they too, many of whom are still living, those who are now priests and missionaries, also have happy memories of that period. When I learned that I was named to Dakar, it was a heavy blow for me, for I knew nothing of Senegal, I knew none of the Fathers there, and I did not know the language of the country, while in Gabon, I knew the language of the country, I knew all the Fathers, and I would certainly have felt much more at home. Perhaps I would even have been capable of a better apostolate toward the missionaries and the Africans of Senegal.

I did not know that a year later yet another nomination awaited me, which was that of Apostolic Delegate. That increased the crosses a little, but at the same time the consolations, because I must say that, during the eleven years from 1948 to 1959 that I was Apostolic Delegate, God filled me with joy in visiting all those dioceses with which I had been charged by the Holy Father. I had to visit them, send reports to Rome, and prepare the nomination of bishops and Apostolic Delegates.

The dioceses confided to me at that time numbered thirty-six, and during the years that I was Apostolic Delegate they increased to sixty-four. What I mean is that it was necessary to divide the dioceses, to name bishops, to name Apostolic Delegates, and then to visit the dioceses, to settle the difficulties that might exist in those territories, and at the same time to get to know the Church. This missionary Church was represented by her bishops, who accompanied me on all the journeys that I made in their dioceses. I was received by the Fathers, and by those who were in contact with the apostolate, with the natives, with the different peoples, and with the different mentalities, from Madagascar to Morocco, because Morocco was also dependent upon the Delegation of Dakar; I travelled from Djibouti to Pointe Noire in Equatorial Africa.

All these dioceses that I had the occasion to visit made me conscious of the vitality of the Church in Africa, for this period between 1948 and 1960 was a period of extraordinary growth. Numerous were the congregations of Fathers and the congregations of Sisters that came to help us. That is why I also visited Canada at that time, and many of the countries of Europe, to attempt to draw men and women religious to the countries of Africa to aid the missionaries, and to make the missions known.

And each year I had the joy of going to Rome and approaching Pope Pius XII. For eleven years I was able to visit Pope Pius XII, whom I venerated as a saint and as a genius - a genius, humanly speaking. He always received me with extraordinary kindness, taking an interest in all the problems of Africa. That is also how I got to know very closely Pope Paul VI, who was at that time the Substitute2 of Pope Pius XII and whom I saw each time that I went to Rome before going to see the Holy Father.

So I had many consolations, and was very intimately involved, I would say, in the interests of the Church - at Rome, then in all of Africa, and even in France, because by that very fact, I had to have relations with the French government, and thus with its ministers. I was received several times at the Elysée, and several times I was obliged to defend the interests of Africa before the French government. I should also say that at that time the Apostolic Delegate, of whom I was the first in the French colonies, was always considered as a Nuncio, and thus I was always given the privileges that are given to diplomats and to ambassadors. I was always received with great courtesy, and they always facilitated my journeys in Africa.

Oh, I could well have done without the detachments of soldiers who saluted me as I descended from the airplane! But if it could facilitate the reign of God, I accepted it willingly. But the African crowds who awaited the Delegate of the Holy Father, the envoy of the Holy Father - in many regions it was the first time that they had received a delegate of the Holy Father - now that was an extraordinary joy. And the fact that the government itself manifested its respect for the representative of the Pope increased still more, I would say, the honor given to the Pope himself and to the Church. All that was, as you can imagine, a great source of joy for me, to see the Church truly honored and developing in an admirable manner.

At that time the seminaries were filling and religious congregations of African Sisters were being founded. I regret that the Senegalese Sister is not here today. She is at St-Luc, but she was unable to come. I know that she would certainly have been happy to take part in this celebration. Yes, the number of Sisters multiplied throughout Africa. All this is to show you once more how God spoiled me during my missionary life.

And then there was the Council, the work of the Council. Certainly it is there, I should say, that the suffering begins somewhat. To see this Church which was so full of promise, flourishing throughout the entire world...I should also add that, from 1962 on, I passed several months in the Diocese of Tulle, which were not useless for me because I was able to become familiar with a diocese of France and to see how the bishops of France reacted and in what environment they were.

I must say that often I was somewhat hurt to see the narrowness of mind, the pettiness of their problems, the tiny difficulties which they considered enormous problems, after returning from the missions where our problems were on a much greater scale, and where the relations between the bishops were much more cordial. In the least matters, you could sense how touchy they were; that was something which caused me pain.

And I was also surprised at the manner in which I was received into the French episcopate. For it was not I who had asked to be a bishop in France. It was Pope John XXIII at that time who obliged me to leave. I begged him to leave me free, to leave me in peace and to let me rest for a while after all those years in Africa. But he would hear nothing of it and he told me, ‘An Apostolic Delegate who returns to his country should have a diocese in his country. That is the general rule. So you should have a diocese in France, so I accepted since he imposed it upon me, and you know what restrictions were placed upon me by the bishops of France and particularly the assembly of Archbishops and Cardinals, who asked that I be excluded from the assembly of Archbishops and Cardinals, although I was an archbishop, that I should not have a big diocese, that I should be placed in a small diocese, and that this would not be considered a precedent. This is one of the things that I found very painful, for why should a confrère be received in such a way, with so many restrictions?

No doubt the reason was because I was already considered a traditionalist, even before the Council. You see, that did not begin at the Council! So in 1962 I spent some time in Tulle. I was received with great reserve; with cordiality, but they were also afraid of me. The Communist newspapers already spoke of me obviously in somewhat less than laudatory terms. And even the Catholic papers were very reserved: what is this traditionalist bishop coming to do in France? What is he going to do at Tulle? But after six months, I believe that I can say that the priests whom I had the occasion to see, to meet...I had the occasion to give Confirmation in almost all the parishes, and our relations were truly excellent. I admired the clergy of France, who were often living in poverty, but who constituted a fervent, a devoted, a zealous clergy, really very edifying.

Then I was named Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers, and there again, I had occasion to travel, this time not only to Africa, but South America, North America, and everywhere where there were Holy Ghost Fathers...the Antilles, all the English territories of Africa and all the English-speaking territories; the Belgian Congo; South Africa; and so on - all of which obviously permitted me to become more familiar with all these missions, and I really believed that God was everywhere pouring forth extraordinary graces on His Church. At that time the effects of the Council, and all this degradation, had not yet begun. So it was a very happy period, very consoling.

Then came the Council and the results of the Council, and, I must say, it was an immense pain for me to see the decline of the Church, so rapid, so profound, so universal, that it was truly inconceivable. Even though we could foresee it, and those who worked with me in the famous Coetus Internationalis Patrum (the International Group of Fathers) did foresee it, the assembly of two hundred and fifty Fathers who strove to limit the damage that could be foreseen during the Council, none of us, I think, could have foreseen the rapidity with which the disintegration of the Church would take place.

It was inconceivable, and it obliged us to admit in a few years how much the Church was affected by all the false principles of Liberalism and of Modernism, which opened the door to practically every error, to all the enemies of the Church, considering them as brothers, as people with whom we had to dialogue, as a people as friendly as ourselves, and thus to be placed on the same footing as we, in a theoretical manner, and even in practice. Not that we do not respect their persons; but as for their errors, we cannot accept them. But you have all been familiar with this portion of history for some time now.

Indeed, I suffered terribly. Imagine if I had remained with the Holy Ghost Fathers where, in theory, I should have stayed until 1974. I could have stayed until 1974 as Superior General. I had been named for twelve years in 1962. But I submitted my resignation in 1968 and, in fact, I was glad to do so, because I did not want to collaborate in the destruction of my congregation. And had I remained Bishop of Tulle, I cannot very well imagine myself at present in a diocese of France! In an environment like that, I should probably have had a nervous breakdown!

It seemed that God intended my apostolic life to end in 1968, and I foresaw nothing else than simply to go into retirement at Rome; indeed, I rented a small apartment at Rome from some Sisters in Via Monserrato, and I was very happy there. But I think that God decided that my work was not yet finished. I had to continue. Well, I could never have imagined - because there I was in a small apartment, which M. Pedroni and M. Borgeat know well - I could never have imagined at that time that God was reserving for me such profound joys and such immense consolations.

For could there be, in my last years, a consolation greater than to find myself surrounded by such faithful collaborators, faithful especially to the Church and to the ideal which we must always pursue; than to find myself surrounded by such devoted, such friendly, and such generous lay people, giving their time and their money and doing all that they can to help us? And besides them, I should recall, we must think of the tens of thousands of benefactors who are with us and who write to us - we receive their letters all the time. Now that is obviously for us and for myself an immense consolation. It is truly a family that has been created around Ecône.

And then, to have such good seminarians! I did not expect that either. I could never imagine or really believe that, in the age in which we live, in the environment in which we live, with all this degradation that the Church is undergoing, with all this disorganization, this confusion everywhere in thought, that God would still grant the grace to young men of having this desire, a profound desire, a real desire, to find an authentic priestly formation; to search for it, to leave their countries to come so far, even from Australia, even from the United States, to find such a formation; to accept a journey of twenty thousand kilometers to find a true Seminary. It is something I could never imagine. How could you expect me to imagine such a thing? I like the idea of an international Seminary and I am very happy with it, but I could never imagine that the Seminary would be what it is and that I would find young men with such good dispositions.

I believe that I can say, without flattering you and without flattering myself, that the seminary strangely resembles the French Seminary that I knew, and I believe that I can even say that it is of a quality even more pleasing to God...more spiritual, especially, and it is that which makes me very happy, because it is the character that I very much desire to give to the Seminary. It is not only an intellectual character, a speculative character - that you should be true scholars...may you be so, certainly, it is necessary - but especially that you should be saints, men filled with the grace of God, filled with the spiritual life. I believe that it is even more essential than your studies, although the studies are indispensable.

For this, then, and for all the good that you are going to do, how can you expect me not to thank God? I ask myself why God has thus heaped His graces upon me. What have I done to deserve all these graces and blessings? No doubt God wished to give me all these graces and blessings so that I could bear my cross more easily.

Because the cross is heavy, after all...heavy in the sense to which I made allusion this morning. For it is hard, after all, to hear oneself called, and to be obliged in a way to accept that people call you, disobedient. And because we cannot submit and abandon our faith. It is a very painful thing, when you love the Church, when you love obedience, when for your entire life you have loved to follow Her leaders and Her guides. It is painful to think that our relations are so difficult with those who ought to be leading us. And all that is certainly a heavy cross to bear. I think that God gives His blessings and graces in compensation, and to strengthen us in our work.

For all this, then, I thank God, first of all, and I thank all of you, and may God do as He pleases. If He wishes me to be at your service yet for some time, let it be so. Deo gratias! If on the other hand He wishes to give me a small reward somewhat sooner, more quickly, well, let it be Deo gratias also. As He wishes. I have worked only in His service and I desire to work to the end of my days in His service and in yours also. So thank you again and let us ask God to grant that this seminary may continue for His glory and for the good of souls."

1. Every Catholic, including priests and members of religious orders, must refuse to obey even the order of a lawful superior if complying with that order could endanger his faith.

2. The assistant to the Vatican Secretary of State is known as the "Substitute".