Life of Archbishop Lefebvre

Marcel Lefebvre was born on November 29, 1905 in Northern France. His father ran a textile mill. After high school, he joined his elder brother at the French seminary in Rome in October 1923. All his life, Archbishop Lefebvre had a great esteem for the rector of the French seminary, Fr Henri Le Floch who taught him to love and revere the teaching of the popes. This priest would explain the great encyclicals written against modern errors such as liberalism, modernism, or communism. On September 21, 1929, Marcel Lefebvre was ordained to the priesthood by Cardinal Liénart in Lille.

He then came back to Rome to prepare his doctorate in theology, while

assuming the office of first master of ceremonies at the seminary. Having already earned his doctorate in philosophy, he obtained a doctorate in theology on July 2, 1930.

From 1930 to 1931, he was assistant to a parish priest in a working-class suburb while awaiting the permission of his bishop to enter the Holy Ghost Fathers (a missionary congregation). On September 1st, he began his novitiate.

He took his vows on September 8, 1932. On November 12 of that same

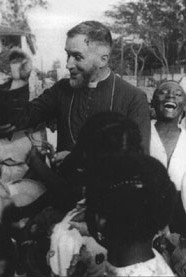

year he embarked for Libreville (Gabon) where he was appointed professor at the seminary, a charge he would keep until he became rector of the same seminary in 1934. In 1938, seeing he was suffering from malaria and quite exhausted, his superior sent him to “the bush to rest”.

From 1938 until 1945, Fr. Marcel was superior of various missions in

Gabon. He showed a keen sense of organization, and proved himself an excellent administrator, careful to modernize installations in order to simplify everybody’s work: for instance he installed generators,

machines, running water…

In October 1945, he was recalled to France to be rector of the philosophical college of the Holy Ghost Fathers in Mortain (Manche). He set to the task of repairing the house, which had suffered from the war, and formed the seminarians according to the teachings of the popes.

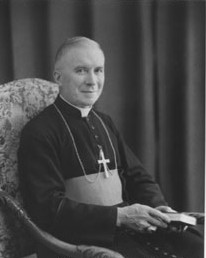

On June 25, 1947, he learnt that he had been appointed Apostolic

Vicar of Dakar, and on Thursday, September 18, 1947 he was consecrated a bishop.

In 1948, Pius XII appointed him Apostolic Delegate (i.e. the equivalent of a nuncio) for French-speaking Africa. Additionally, as the delegate needs to be an archbishop, Bishop Lefebvre was appointed titular archbishop of Arcadiopolis in Europa. He was the pope’s representative in one diocese, 26 vicariates, and 17 apostolic prefectures, over a territory going from Morocco and the Sahara to Madagascar and Reunion, through French West Africa and French Cameroon, Equatorial French Africa and Somalia, that it is to say a Catholic population of over 2 million faithful.

In 1949, in the square before the cathedral of Dakar, the minister for the French Overseas Territories came to present him with the cross of the Knights of the Legion of Honor.

In 1962, he was transferred from the archiepiscopal see of Dakar to

the episcopal see of Tulle in France with the personal title of Archbishop. The French bishops had lobbied in Rome against his appointment as archbishop of Albi, which was originally considered, and

they had only accepted his return to the mother country on condition that he be sent to a small diocese. They did not want him because of his

“integrist leanings”.

In Tulle, prospects were bleak. Vocations were on the decline, as

well as religious practice. The priests were living in dire poverty and becoming discouraged. Archbishop Lefebvre considered energetic measures. He encouraged his priests, visited them, and gave them his support. He was very much impressed by the difference between the flourishing mission he had left and the desolation he was finding in France. But in July 1962, Archbishop Lefebvre was elected Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers by a comfortable majority.

On January 25, 1959, Pope John XXIII announced the meeting of a council. Archbishop Lefebvre was appointed among the members of the Central Preparatory Commission of the Council. He attended all the meetings, which were even at times presided over by the pope, and he witnessed clashes, sometimes violent, between the liberal tendency and the conservative members of the Commission. This seemed to him a bad omen.

As Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers, he fought against the falling-off of discipline and theological deviations. Unfortunately, it was again without complete success, because the men he appointed to various offices were not always worthy of his confidence. He reformed the organization of his congregation, transferred the Mother House to Rome, traveled far and wide to visit his houses, organizing and encouraging his religious.

For several years, priests and more especially seminarians looking

for a serious formation had had recourse to him. Some he directed to the French seminary in Rome run by the Holy Ghost Fathers, which he had hoped he could keep doctrinally sound. Alas, such was not the case, the rector of the seminary making but little account of the advice of his superior. Others he later sent to a priestly society established in Rome, and others still to the Catholic university of Fribourg, in

Switzerland. As young priests and seminarians kept insisting that he undertook a work in favor of the priesthood, he left the decision to the bishop of Fribourg, who readily authorized him to open a refuge for seminarians from all countries. The seminary was born. Archbishop Lefebvre rented twelve rooms at the Don Bosco House in Fribourg and welcomed his first candidates on October 13, 1969. The beginnings were

difficult, many seminarians left, and Archbishop Lefebvre became seriously ill.

On November 1st, 1970, Mgr François Charrière, bishop of Fribourg, The classes at the University of Fribourg being unsatisfactory,

Archbishop Lefebvre obtained from the bishop of Sion permission to

establish in Ecône a seminary, which would grow rapidly.

Considering the distress and discouragement of numerous Catholics

confronted with the disappearance of the faith, the havoc created in the

liturgy and the utter loss of the sense of the divine, Archbishop

Lefebvre took up his missionary staff and began his journeys in Europe

and all over the world. He would give conferences, and encourage

confused faithful and persecuted priests to create associations and to

keep the Faith without compromise.

In 1973, upon the request of an young Australian lady, Archbishop Lefebvre, with the help of his sister, Mother Marie Gabriel, a Holy Ghost Sister, founded a society of Sisters, about which he had already thought when writing the statutes of the Society. Such was the origin of the Sisters of the Society of Saint Pius X. They settled in the house that had been acquired in Albano, in the suburbs of Rome. Their vocation was to be the discreet and efficient helpers of the priests, while living a semi-contemplative life (one hour of adoration per day). The foundation of the brothers of the Society and of the Oblate Sisters occurred at the same time as that of the Sisters of the Society. As early as 1971, some pious lay people had asked Archbishop whether he would establish a Third Order. It was finally erected in 1981, according to the rules drawn by the founder.

On November 11, 1974, an apostolic visitation took place in Ecône, following some complaints from the French bishops against this seminary which kept the Mass and tradition and which was receiving vocations while their own seminaries were emptying. On November 21, 1974, in a forceful declaration (link here) he stated his adhesion to eternal Rome and his refusal of the “Rome of neo-Modernist and neo-Protestant tendencies which manifested itself during Vatican II and after the council in all the reforms which issued from it…”

Archbishop Lefebvre was called to Rome for an “interview”, which was nothing less than a trial. On May 6, the Society was illegitimately “suppressed”. Archbishop Lefebvre appealed to the Supreme Apostolic Signatura (the highest ecclesiastical court). But Cardinal Jean Villot, Secretary of State, intervened to stop the canonical process. Calmly and peacefully, in the face of this denial of justice, the prelate decided to carry on with his work, considering that the Society continued to exist since its suppression was irregular and in any case unjust.

In June 1976, disregarding the threats from Rome, and judging that the fight he was leading was fundamental for the defense of the Mass and of the Faith, Archbishop Lefebvre ordained 13 priests and 14 sub-deacons

without dimissory letters. He was punished with a suspens a divinis, which ought to have deprived him of the exercise of any sacramental act. This sanction did not trouble him or catch him off-guard. In a supernatural vision of his duty, he decided to keep up the good fight against all the deviations, which were already shaking the Church.

On August 29, he celebrated a public solemn High Mass in Lille, before 7000 faithful. The media made much ado about it, and called him the “rebellious” bishop. (Part of Sermon Here)

Nevertheless, he was granted an audience by Paul VI on September 11. There he discovered that he had been seriously calumniated. However, the pope did not want to make room for the Mass of St Pius V, being anxious to impose “his own” reform, while Archbishop Lefebvre, for the sake of fidelity to the Church of all times did not want and could not accept the “conciliar” Church, nor the new Mass.

In September 1976, he published his book I Accuse the Council On November 18, 1978, hardly a month after his election, Pope John Paul II received Archbishop Lefebvre. The interview began well, but the intervention of Cardinal Seper, Head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, spoiled everything. And besides, the pope

entrusted the case to that cardinal. Thus began a process, which would drag on for years. The founder of Ecône would often go to Rome to explain himself and to try to obtain a return to tradition, the guardian

of the Faith, or at least freedom for the Society to follow tradition. But neither Cardinal Seper, nor his successor, Cardinal Ratzinger, would prove ready to make any gesture in that direction.

In 1983, Archbishop Lefebvre, already progressively disappointed by the texts of Pope John Paul II, tainted with modernism, was deeply scandalised by the new Code of Canon Law, which codified into law the deviations of the Council. He then seriously considered the consecration

of bishops and engaged upon the path of public protestation against the scandals perpetrated at the very summit of the Church.

In 1985, Archbishop Lefebvre submitted his dubia to Rome: thirty-nine propositions, or “doubts” concerning the discrepancies

between the conciliar doctrine on religious liberty and the previous teaching of the Church.

In October 1986 took place the awful scandal of Assisi, which Archbishop Lefebvre answered in a joint letter with Bishop de Castro Mayer.

In March 1987, he received Rome’s answer to the dubia. It was an unsatisfactory answer. In June 1987, the Archbishop published a book dealing with the destruction of the social kingship of Christ, They Have Uncrowned Him: In June 29, 1987, Archbishop Lefebvre made public his intention to give himself successors in the episcopate. The answer to the dubia was the sign he was waiting for, and he explained that it was more serious to affirm false principles than to accomplish a scandalous act. He then appointed the feast of Christ the King as the date for the consecration.

Rome then reacted and proposed the visit of a cardinal who would merely have an informative mission. Archbishop Lefebvre accepted the visitor and communicated the news to the 4000 faithful who had come to attend the Mass of thanksgiving for his 40 years of episcopacy, on October 3.(link here) Archbishop Lefebvre plainly stated his demands. On February 2, he

confirmed that he would consecrate at least three bishops for the good of the Church and the perpetuity of Tradition, with or without the approval of the Pope. Negotiations began in Rome between the representatives of the Society and members of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. This led to the signing of a protocol of agreement with Rome on May 5. But, soon realizing that Cardinal Ratzinger was not ready to grant him what he was asking for, the Archbishop recanted. He consulted with others, and on June 2, 1988, he wrote to the pope to tell him his decision to consecrate 4 bishops on June 30.

On June 30, he consecrated four bishops before 10,000 faithful and a crowd of journalists. During the ceremony, Archbishop Lefebvre explained the necessity in which he found himself to transmit the episcopacy, for the good of the Church and despite the opposition from the hierarchy.(link here) The excommunication, logical in the mind of the Roman authorities, was pronounced the following day, but it missed its mark. It did nothing more than underline the powerlessness of a modernism which had formerly been triumphant, but was already decaying the Church and filling it with its stench.

During the three years that God granted him from 1988 till his death, Archbishop Lefebvre gave his four young auxiliaries the support of his moral presence; he introduced his future heirs to their new office, leaving them the task of conferring ordinations, which he attended in

all modesty.

But his health was failing. He made a last intercontinental journey

to Gabon in 1990. In February 1991, he gave his last conference to the seminarians of Ecône. On March 8, he celebrated his last Mass and left for Paris. But during the night of March 9, he woke up his chauffeur and asked him to drive him back to Switzerland. He was taken to the emergency room of the hospital in Martigny. On March 18, he underwent surgery. On Palm Sunday, March 24, his state of health suddenly became worse.

On March 25, 1991, feast of the Annunciation which that year fell on

Monday of Holy Week, at 3:25 am, while the Superior General and Fr. Simoulin, rector of Ecône, were praying at his bedside, Archbishop Lefebvre gave back his soul to God.

At least once a year, the apostolic delegate would give the pope an account of his actions and receive his guidance. Thus, Archbishop Lefebvre became acquainted with the various dicasteries of the Roman Curia. At the Secretariat of State, to which he would report as a diplomat, Archbishop Lefebvre had dealings with the two under-secretaries: Mgr Tardini and Mgr Montini; this latter would receive the Delegate politely but without showing any sympathy for his

ideas.

At least once a year, the apostolic delegate would give the pope an account of his actions and receive his guidance. Thus, Archbishop Lefebvre became acquainted with the various dicasteries of the Roman Curia. At the Secretariat of State, to which he would report as a diplomat, Archbishop Lefebvre had dealings with the two under-secretaries: Mgr Tardini and Mgr Montini; this latter would receive the Delegate politely but without showing any sympathy for his

ideas.

After the election of John XXIII he was relieved of his office as Apostolic Delegate but remained archbishop of Dakar. However, his unflinching frankness in defending the teaching of the popes and in denouncing the “Catholic socialism” of president Senghor provoked the anger of this latter and doubtless contributed to hasten his demission, which was (privately) desired by Rome.

After the election of John XXIII he was relieved of his office as Apostolic Delegate but remained archbishop of Dakar. However, his unflinching frankness in defending the teaching of the popes and in denouncing the “Catholic socialism” of president Senghor provoked the anger of this latter and doubtless contributed to hasten his demission, which was (privately) desired by Rome.

During the council, confronted with the importance gained by the modernist theses, which received the support of a veritable lobby, which was well prepared and organized1, he founded the Cœtus internationalis Patrum

with a few other bishops and was appointed its president. He became acquainted with Bishop Antonio de Castro Mayer, bishop of Campos in Brazil, who would also become a member of the Cœtus. By his actions in

the Cœtus and by his interventions at the conciliar sessions, he fought against the modernist influence spreading over the council, but alas the results proved insufficient.

During the council, confronted with the importance gained by the modernist theses, which received the support of a veritable lobby, which was well prepared and organized1, he founded the Cœtus internationalis Patrum

with a few other bishops and was appointed its president. He became acquainted with Bishop Antonio de Castro Mayer, bishop of Campos in Brazil, who would also become a member of the Cœtus. By his actions in

the Cœtus and by his interventions at the conciliar sessions, he fought against the modernist influence spreading over the council, but alas the results proved insufficient.

In 1965 began the aggiornamento of the religious congregations demanded by the council. Archbishop Lefebvre meant it to be an opportunity for straightening out deviations and increasing the holiness ofreligious life. He was far from being against all reforms even the most daring, as long as they were faithful to the ideal of the founder. At the General Chapter of his congregation, in 1968, attempts were made to set him aside and the prevailing majority was in favor of disastrous reforms. To avoid signing decrees, which would have brought his congregation in line with the reigning fashion, Archbishop Lefebvre left the Chapter, after the election of his successor, and withdrew to a small boarding-house run by Sisters, in Rome. He was then sixty-three.

In 1965 began the aggiornamento of the religious congregations demanded by the council. Archbishop Lefebvre meant it to be an opportunity for straightening out deviations and increasing the holiness ofreligious life. He was far from being against all reforms even the most daring, as long as they were faithful to the ideal of the founder. At the General Chapter of his congregation, in 1968, attempts were made to set him aside and the prevailing majority was in favor of disastrous reforms. To avoid signing decrees, which would have brought his congregation in line with the reigning fashion, Archbishop Lefebvre left the Chapter, after the election of his successor, and withdrew to a small boarding-house run by Sisters, in Rome. He was then sixty-three.

In June 1970, he bought a house, in Fribourg again, to accommodate

his seminarians that were to carry on their studies at the university. But, at the same time, with the permission of Msgr. Adam, bishop of Sion, he accepted the house of Ecône, which was offered to him by its

owners, in order to open a year of spirituality for the newcomers (in accordance with the council in its decree on priestly formation).

In June 1970, he bought a house, in Fribourg again, to accommodate

his seminarians that were to carry on their studies at the university. But, at the same time, with the permission of Msgr. Adam, bishop of Sion, he accepted the house of Ecône, which was offered to him by its

owners, in order to open a year of spirituality for the newcomers (in accordance with the council in its decree on priestly formation). approved the statutes written by Archbishop Lefebvre for the Society of Saint Pius X, and erected it in his diocese. The goal of the Society, as expressed by its statutes, is “the priesthood and all that pertains to it and nothing but what concerns it”.

approved the statutes written by Archbishop Lefebvre for the Society of Saint Pius X, and erected it in his diocese. The goal of the Society, as expressed by its statutes, is “the priesthood and all that pertains to it and nothing but what concerns it”.

On November 11, Cardinal Gagnon began his visit, which would end on

December 8 in Ecône. The cardinal did not hesitate to attend the Pontifical Mass of the suspended archbishop during which young men made their commitment into a (supposedly) suppressed Society! As far

as we know, the report of the visitor was favorable.

On November 11, Cardinal Gagnon began his visit, which would end on

December 8 in Ecône. The cardinal did not hesitate to attend the Pontifical Mass of the suspended archbishop during which young men made their commitment into a (supposedly) suppressed Society! As far

as we know, the report of the visitor was favorable.

1..Refer to the Book by Ralph M. Wiltgen,here

The Rhine Flows into the Tiber