By Thomas Acres

The most effective writing came from the pen of Father John England, destined to be one of America's foremost bishops, he was liberal and forthright with experience as to the plight of transportees. He wrote a series of articles in the "Cork Chronicle" giving an historical survey of the work he had done for Irish transportees. He told also of how he had obtained a promise from authorities that a Catholic mission should be sanctioned in New South Wales. He had known Father O'Flynn before his departure to New South Wales and with vigour launched an appeal to the authorities demanding legal status for the Catholic church in Australia.

Two years later he was named First Bishop of Charleston, South Carolina. His open letter written on January 5, 1819, produced immediate results, and may be regarded as one of the instrumental causes for the foundation of the Catholic church in Australia.

An enquiry was undertaken into the conditions in New South Wales, which took two years and was undertaken by John Thomas Bigge, who regarded the settlement purely as penal where free men should be treated as a superior class. He strongly opposed the emancipist policy and Macquarie's building policy. Having wide powers his presence soon became intolerable for the old autocrat who resigned and sailed home to England before the completion of the report.

The enquiry also dealt with the situation of the Catholics and the results of his report to the English authorities was that colonial autocracy was overturned making way for constitutional government. This would thus make way for freedom of conscience for Catholics and a subsidised Catholic Mission in New South Wales, when in England such freedoms were a mere dream.

Thus the way was clear for the foundation of the Catholic church in Australia. Jeremiah O'Flynn became the unconscious reformer of British social policy in Australia. He spent his last years in the West Indies and the United States of America, where he was finally admitted into the diocese of Philadelphia. He built the first Catholic church in Susquehanna County at Silver Lake in 1828 and died on February 8, 1831 aged 42 years.

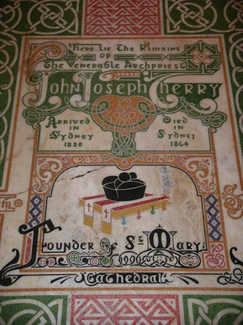

When Bigge was travelling around the colony gathering information for his report, two Catholic priests arrived in the colony, John Joseph Therry and Phillip Connolly. On May 7, 1820 Father Connolly celebrated Mass in a house on Pitt Row and on May 8 Father Therry offered Holy Mass for the Glory of God and Saint Michael. It is thought that he also found the Blessed Sacrament left in the Oak Press by his predecessor Father O'Flynn. This miraculous preservation of the Sacred Species was hailed by the Catholic population as a miracle and the arrival of the priests was a mercy that they had yearned for as an answer to prayers. They had hoped that God would allow them to be forever shut out from the blessing of His Holy Church.

Though in time the Protestants sneered at such beliefs, the arrival of the two priests caused little anxiety to them. Even Macquarie confined himself to report that the two priests had arrived with the permission of the government and had come as passengers of the "Janus". In fact the Protestant community felt inclined to help more than to hinder the work of the Catholic priests. A Protestant, by the name of John Piper, helped them find board and lodging. Then in a public meeting held on June 30 Protestants agreed to unite with Catholics to raise money to build a church. The first signs of Australian friendliness were beginning to show forth in the people of the colony.

On June 6, 1820 Macquarie informed Fathers Connolly and Therry of the restrictions on freedom in New South Wales. The could celebrate Mass; marry two Catholics but not a Catholic and Protestant; they could baptize the children of Catholic parents, but they were not to try and win converts; they were not to concern themselves with the religious education of children in the government institutions of the colony, who were to be instructed in the faith and doctrine of the Church of England.

Meanwhile Father Connolly to Van Diemans Land. Father Therry remained on the mainland, saying Mass every Sunday at Parramatta and Liverpool, giving instruction in the Faith, visiting the sick and giving extreme unction to those in danger of death, with a circuit of 200 miles. Once, word was brought to Father Therry that a convict sentenced to death wanted to see him for confession. Father Therry immediately mounted his horse and set out for Sydney. But a bridgeless river which he had to cross was in a raging flood and impossible to ford on horseback . He called for help, "in the name of God and departing soul," to a man on the other bank. A rope tied to a stone was thrown across and fastening it around his body he was dragged through the swollen stream to the other side. Without rest or change of clothing, he immediately mounted another horse and arrived in time to attend to the condemned man. By such acts of heroism and devotion to duty, as well as a boundless charity Father Therry demonstrated that the image of Christ lived in the sons of the church.

The work of Father Therry was most vividly shown in his apostolate to the convicts. It had a three fold character; firstly, a personal mission to individual convicts; secondly, an appeal for pardon or revisions of sentences; thirdly, demands for a strict adherence to the law in the matter of evidence, procedures and punishment. His personal apostolate became a legend in the colony. He became the felons' friend, attending to them in prisons, hospitals and chain gangs. When bushrangers and escaped convicts intercepted him on one of his missionary journeys, they would immediately release him with expression of regret and allow him to pass on his way. Despite the length of his circuit, he was always at the beck and call of the convicts.

He knew each convict individually in the prisons, and his figure passing from cell to cell became part of the gaol routine. But soon the work of Father Therry was suspended and he could no longer count on concessions and favours for the convicts. Still, Father carried on perseverance and not a little ingenuity. On one occasion, for example, he was called to a dying person only to find the bayonet of a guard blocking his entrance. He asked the guard if he was willing to take the death of a person on his shoulders: "it is not in the name of the Government I come here but in the name of God." The guard lowered his bayonet and Father Therry passed on.

Part V Prev Part III