By Thomas Acres

Father O'Flynn entered the colony in the height of the autocratic rule of Lachlan Macquarie (1810-1821). Macquarie was a rugged and overbearing Scot, who transformed the life of Sydney in the course of a decade. he hastened to assimilate the emancipated convicts into the society granting them land, admitting them to professions and even inviting them to social functions. This policy greatly favoured the Catholics, most of whom were ex-convicts, thus enabling the Rebels of '98 to become prominent citizens of Sydney.

The free settlers did not approve at all of this policy, thus a bitter feud was underway when Father O'Flynn stepped ashore on November 9, 1817. Macquarie received this intruder with official courtesy, but flatly refused him to perform his ministry. He prohibited him from saying Mass in public, but delayed any other action till he received word from London. Well, after all he did have the title of Prefect-Apostolic from Rome. in Sydney at the time there were around six thousand Catholics, who were a despised minority with very little influence. But besides this small size they found themselves in the centre of a popular movement in his support, petitions were signed and presented to the Governor, but Macquarie remained unmoved, and a warrant for his deportation was served on December 12, 1817.

Father O'Flynn, in order to forestall his deportation 'went bush', which very much tried Macquarie's patience. Another vessel was prepared and after a ten day cat and mouse game with the police Father O'Flynn was eventually arrested and lodged in a common goal. Then on May 20, 1818, he was put aboard the 'David Shea' heading for London, and Governor Macquarie recorded bluntly in his diary: 'O'Flynn, the popish missionary, was this day sent back to England."

During father's six month stay in Sydney he carried on a busy underground apostolate which has become the most vivid and inspiring tradition in the story of the Catholic Church in Australia. He performed his priestly function in secret, saying Mass in a small room of a settlers cottage, with nine or ten people in attendance. For the first time in ten years the faithful could receive the sacrament of Penance and Holy Eucharist, obtain the Church's blessing on their marriage, have their children baptised, and even receive the Sacrament of Confirmation, for which the missionary had special faculties.

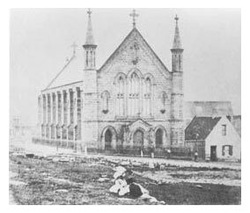

But he is most vividly remembered for his role in the story of the 'Holy House of Australia.' tradition has it that before his arrest and deportation, he left the Blessed Sacrament, reserved for the sick, in a cedar press in the cottage of William Davis, (site of St Patrick's Church today) an Irish Blacksmith who was transported for making pikes for the Rebels of '98. For two years after his departure, with the nearest priest six thousand miles away, a lamp was kept burning before the humble tabernacle, and with inspiring faith and fervour the little band of Catholics would gather in secret for devotions. The story is an historically true fact that Father O'Flynn left the Blessed Sacrament in Sydney.

When Father O'Flynn arrived in London he presented a "humble remonstrance and petition of the Roman Catholics of New South Wales" pleading that a priest be sent to them in their plight. His own personal petition for official recognition was dismissed by the Home Office, and the failure of his mission seemed to be complete. But God was to draw from this seeming failure in man's eyes a curious triumph. Father O'Flynn was to become the silent, passive and mostly unconscious reformer of the policy concerning the colonies.

He arrived in England when new liberal and democratic ideas were gaining ground in the political arena. Thus the story of Father's plight was received with sympathy amongst those wishing reform. It touched off a newspaper and political campaign in England and Ireland for the plight of colonial Catholics and the horrors of transportation.

Part IV Prev Part II