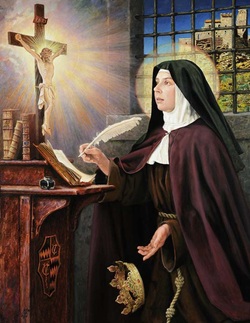

An ascetical writer, born at Camerino, in the March of Ancona, 9 Apr., 1458; died there, 31 May, 1527.

Her father, Julius Caesar Varano or de Varanis, Duke of Camerino, belonged to an illustrious family; her mother, Joanna Malatesta, was a daughter of Sigismund, Prince of Rimini.

At baptism Baptista received the name of Camilla. Of the first ten and the last twenty-three years of her life little or nothing is known; our knowledge of the intervening years is derived almost entirely from her own writings. This revelation of herself was brought about through the influence of her confessor, Blessed Peter of Mogliano, provincial of the Franciscans in the Marches (1490). It seems to have been the eloquence of Mogliano that brought about the “conversion” of Baptista, who, for a time at least, appears to have been captivated by the glamour of the world. Her father did all in his power to force his daughter into a brilliant marriage, even to the extent of imprisoning her. But Baptista resisted his plans so firmly that after two years and a half he restored her to liberty, for fear, as he said, of drawing upon himself the Divine vengeance, and gave his consent to her becoming a nun. On 14 Nov., 1481, Baptista entered the monastery of the Poor Clares at Urbino. Not long afterwards her father founded a new monastery of that order at Camerino, and presented it to his daughter. Baptista introduced the primitive observance of the rule there, and thenceforth her vigorous and impressive personality found scope not only in the administration of this monastery, of which she became the first abbess, but also in the production of various literary works. These include the: “Recordationes et instructiones spirituales novem”, which she wrote about 1491; “Opus de doloribus mentalibus D.N.J.C.”, written during 1488-91 and first published at Camerino in 1630; “Liber suae conversionis”, a story of her life, written in 1491, and first published at Macerata in 1624. These works have been edited by the Bollandists in connection with some of Baptista’s letters. But most of her “Epistolae spirituales ad devotas personas” as well as her “Carmina pleraque latina et vulgaria” are still unpublished.

As a whole the writings of Baptista are remarkable for originality of thought, striking spirituality, and vividly pictorial language. Both St. Philip Neri and St. Alphonsus have recorded their admiration for this gifted woman who wrote with equal facility in Latin and Italian, and who was accounted one of the most brilliant and accomplished scholars of her day. Baptista died on the feast of Corpus Christi, and was buried in the choir of her monastery. Thirty years later her body was exhumed and was found in a state of perfect preservation. It was reburied to be again exhumed in 1593. The flesh was then reduced to dust but the tongue still remained quite fresh and red. The immemorial cultus of Baptista was approved by Gregory XVI in 1843, and her feast is kept in the Franciscan Order on 2 June.