1. (OHS 1956): A blessing of the Paschal candle is introduced using a candle that has to be carried by the deacon during the entire ceremony.

Commentary: When this reform came into effect all the Paschal candlesticks in Christendom were rendered useless for Holy Saturday itself, even though some dated back to the dawn of Christianity. Under the pretext of returning to the sources, such liturgical masterpieces from antiquity became unusable museum pieces. The three-fold chanting of “lumen Christi” [“The light of Christ”] no longer has a liturgical reason to exist.

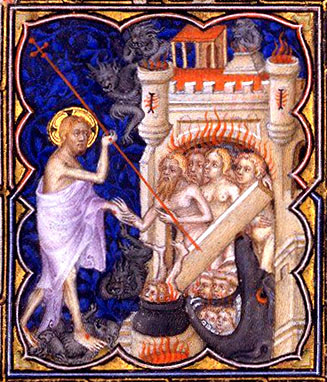

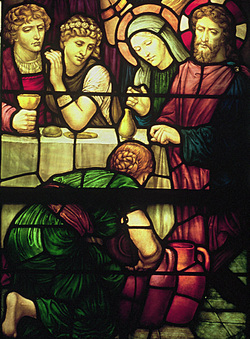

(MR 1952): The new fire and the grains of incense are blessed outside the church, but not the candle; the fire is passed to a reed, a kind of pole with three candles at the top, which are lit during the procession, successively with each invocation of “lumen Christi”; hence the three-fold invocation, one for each candle as it is lit. With one of these candles was lit the Paschal candle, which remained from the beginning of the ceremony on the Paschal candlestick. (In many early Christian churches, the height of the candlestick required the ambo to be built to the same height so that the candle could be reached.) [See the picture below. CAP.] The fire (the light of the Resurrection) was brought in on the reed with its triple candle (the Holy Trinity) to the great Easter candle (the Risen Christ), in order to symbolize the Resurrection as the work of the Most Holy Trinity.

Ambo and Paschal candelabrum

2. (OHS 1956): The fabrication of placing the Easter candle in the center of the sanctuary after a procession with it in a church that is progressively lit up at every invocation of “Lumen Christi” [“The light of Christ”]; and at every invocation all genuflect toward the candle [sic!]; at the third invocation, the lights in the entire church are lit.

Commentary: After the fabrication of a procession with the candle, it was decided to have it placed in the center of the sanctuary, where it becomes the reference point of the prayers, just as it was during the procession; it becomes more important than the altar and the cross, a strange novelty that shifts the orientation of prayer in successive stages.

(MR 1952): The candle remains unlit on its candelabrum, often (according to a rubricist I consulted, this should be "always". CAP) at the Gospel side; the deacon and subdeacon go up to it with the reed to light it during the singing of the praeconium [i.e., “Exsultet”]; until the singing of the “Exsultet,” the only candles lit from the “fire of the Resurrection” are those on the reed.

The singing of the Exultet

3. (OHS 1956): A twisting of the symbolism of the “Exsultet” and of its nature as a diaconal blessing.

Commentary: Some reformers wished to do away with this ceremony, but the love which the singing of the “Exsultet” was always enjoyed resulted in others opposing any change in the text: “the Commission, however, considers it opportune to preserve the traditional text, given that the passages to be eliminated are few and of little importance.” The result was the nth pastiche of a traditional chant wedded to a rite now totally altered. Thus it happened that one of the most significant moments of the liturgical cycle became a theater-piece of astonishing incoherence.

In effect, the actions spoken of during the singing of the “Exsultet” have already been performed about a half-hour before in the narthex. For the grains of incense there is sung: “Suscipe, Pater, incensi hujus sacrificium vespertinum” [“Accept, Father, the evening sacrifice of this incense”], but they have already been inserted into the candle for a good while. The lighting of the candle with the light of the Resurrection is elaborated with the words: “Sed jam columnae hujus praeconia novimus quam in honorem Dei rutilans ignis accendit” [“But now we know the tidings of this column which the flickering fire lights to the honor of God”], but the candle has long been lit by then and a goodly amount of wax consumed. There is no longer any logic. The symbolism of the light is twisted even further when the order of lighting all the lights—the symbol of the Resurrection—is triumphantly chanted: “Alitur enim liquantibus ceris, quas in substantiam pretiosae hujus lampadis apis mater eduxit” [“For it is nourished by the flowing wax which the Mother bee has drawn out unto the substance of this precious Light”], but it is sung in a church which for quite some time has been totally illuminated by the candles lit from the new fire.

This reformed symbolism is incomprehensible for the simple reason that it is not symbolic: the words being proclaimed have no relation to the reality of the rite. Furthermore, the singing of the Easter proclamation, in union with the actions that accompany it, constitutes the diaconal blessing par excellence. After the reform, the candle is blessed outside the church with holy water, but it was desired to retain a part of the ancient blessing since it had great esthetic beauty; unfortunately, this approach reduces the liturgy to theater.

(MR 1952): The singing of the “Exsultet” begins with the candle unlit; the grains of incense are fixed in it when the chant speaks of the incense; the candle is lit by the deacon and the lights in the church are lit when the chant makes mention of these actions. These actions, in union with the chant, make up the blessing.

4. (OHS 1956): Introduction of the unbelievable practice of dividing the litanies in two, in the midst of which the baptismal water is blessed.

Commentary: This decision is simply extravagant and incoherent. Never was it known that an impetratory prayer was split into two parts. The introduction of the baptismal rites in the middle is of an even greater incoherence.

(MR 1952): After the blessing of the baptismal font is finished, the litanies are sung before the beginning of Mass.

5. (OHS 1956): Introduction of placing the baptismal water in a basin in the middle of the sanctuary, with the celebrant turned towards the faithful, his back to the altar.

Commentary: Basically, it was decided to substitute the baptismal font with a pot placed in the middle of the sanctuary. This choice was dictated, once again, by the obsession that all the rites should be carried out with the “sacred ministers facing the people,” but with their back towards God; the faithful, by this logic, become the “true actors of the celebration …. The Commission was receptive to the aspirations poured out by the people of God …. The Church was open to the ferment of renovation.” These reckless decisions, founded on a pastoral populism that the people never requested, ended by destroying the entire sacred edifice, from its origins until the present.

At one time, the baptismal font was outside the church or, in succeeding ages, inside the walls of the edifice but close to the main door, since, according to Catholic theology, Baptism is the door, the “janua Sacramentorum” [“the door to the Sacraments”]. It is the Sacrament that makes those still outside the Church members of the Church. As such, it was symbolized in these liturgical customs. The catechumen receives [in Baptism] the character that makes him a member of the Church; therefore, he is to be received at the entrance, washed in the baptismal water, and thus acquire the right to enter into the nave as a new member of the Church, as one of the faithful. But, as a member of the faithful, he enters only the nave and not the sanctuary, wherein are the clergy, who are composed of those with the ministerial priesthood or who stand in relation to it. This traditional distinction was insisted on because the so-called “common” priesthood of the baptized is distinct from the ministerial priesthood and is distinct essentially, not superficially. They are two different things, not degrees of one single essence.

With the mandated changes, however, not only the baptized (as was already done on Holy Thursday) but even the non-baptized are summoned into the sanctuary, a place set aside for the clergy. One who is still “prey to the demon,” because still with Original Sin, is treated just like one who has received Holy Orders and enters into the sanctuary even though still a catechumen. The traditional symbolism, consequently, is completely massacred.

(MR 1952): The blessing of the baptismal water is given at the baptismal font, outside the church or near the entrance. Any catechumens are received at the entrance of the church, given Baptism, and then bid enter the nave, but not the sanctuary, as is logical, neither before nor after their Baptism.

6. (OHS 1956): Alteration of the symbolism of the chant “Sicut cervus” [“Like the hart that yearns”] of Psalm 41.

Commentary: After the creation of a baptistery inside the sanctuary, one is confronted with the problem of carrying away the baptismal water to some other location. It was decided, accordingly, to contrive a ceremony for carrying the water to the font after blessing it in front of the faithful and especially after conferring any baptisms as there might be. The transport of the baptismal water is accomplished while “Sicut cervus” is sung, i.e. that part of Psalm 41 which speaks of the thirst of the deer after it has fled from the bite of the serpent and which can only be slaked by drinking the water of salvation. At any rate, insufficient attention was paid to the fact that the deer’s thirst is sated by the waters of Baptism after the bite of the infernal serpent; for if Baptism has already been conferred, then the deer no longer thirsts, since, figuratively speaking, it has already drunk! The symbolism is changed and thus turned on its head.

(MR 1952): At the end of the singing of the prophecies, the celebrant goes to the baptismal font, to continue with the blessing of the water and to the conferral of Baptism as necessary; meanwhile, the “Sicut cervus” is sung. (127) The chant precedes, as is logical, the conferral of Baptism.

7. (OHS 1956): Creation ex nihilo of the “Renewal of Baptismal Promises.”

Commentary: One is, in a certain sense, proceeding blind when devising pastoral creations that have no true foundation in the history of the liturgy. Pursuing the notion that the Sacraments ought to be re-enlivened in the conscience, the reformers thought up the renewal of the baptismal promises. This became a kind of “examination of conscience” concerning the Sacrament received in the past. A similar tendency was observed in the twenties of the last century. In a veiled polemic with the provision of St. Pius X concerning the communion of children, the singular practice of a “solemn communion” or “profession of faith” was introduced; children of around thirteen years had to “remake” their first communion, in a kind of examination of conscience on the Sacrament already received several years before. This practice—although without calling into question the Catholic doctrine of “ex opere operato” [“from the work performed”]—emphasized the subjective element of the Sacrament over the objective. The new practice eventually ended up obscuring and overshadowing the Sacrament of Confirmation. A similar approach will be encountered in 1969 with the introduction on Holy Thursday of the “renewal of priestly promises.” With this latter practice is introduced a linkage between sacramental Holy Orders and a sentimental, emotional order, between the efficacy of the Sacrament and an examination of conscience, something rarely encountered in tradition.

The substrate of these innovations—which have no foundation either in Scripture or in the practice of the Church—seems to be a weakened conviction of the efficacy of the Sacraments. Although not in itself a plainly erroneous innovation, it appears nonetheless to lean towards theories of Lutheran provenance, which, while denying that “ex opere operato” has any role to play, hold that the sacramental rites serve more to “reawaken faith” than to confer grace.

It is difficult, moreover, to understand what was actually being sought with these reforms, since in fact edits were made to shorten the length of the celebrations, but tedious passages were introduced which burden the ceremonies unduly.

(MR 1952): The renewal of baptismal promises does not exist, just as, in this form, it has never existed in the traditional history of the liturgy of either East or West.

8. (OHS 1956): Creation of an admonition during the renewal of promises, which can be recited in the vernacular.

Commentary: The tone of this moralizing admonition betrays all too well the era in which it was composed (the mid-fifties). Today it already sounds dated, besides being a rather tedious adjunct. There is also the typical a-liturgical manner of turning to the faithful during this rite, a hybrid between homily and ceremony (which will enjoy great success in the years to follow).

(MR 1952): Does not exist.

9. (OHS 1956): Introduction of the Our Father recited by everyone present, and possibly in the vernacular.

Commentary: The Our Father is preceded by a sentimental-sounding exhortation.

(MR 1952): Does not exist.

10. (OHS 1956): With no liturgical sense whatsoever, there is introduced here the second part of the litany, broken off at the half-way point prior to the blessing of the baptismal water.

Commentary: Before the blessing of the baptismal water, the litany is recited kneeling; afterwards, a great number of ceremonies are performed, along with movements in the sanctuary; then there is the joy following the blessing of the baptismal water and any Baptisms that follow; and then the same impetratory prayer of the litany is resumed at the precise point where it was broken off a half-hour before and left hanging. (It would be difficult to determine if the faithful remember when they left this prayer half-finished.) This innovation is incoherent and incomprehensible.

(MR 1952): The litany, recited integrally and without interruption, is chanted after the blessing of the baptismal font and before Mass.

11. (OHS 1956): Suppression of the prayers at the foot of the altar, the Psalm “Judica me” (Ps. 42), and the Confiteor at the beginning of Mass.

Commentary: It was decided that Mass should begin without the recitation of the Confiteor or the penitential psalm. Psalm 42, which recalls the unworthiness of the priest to ascend to the altar, was not appreciated, perhaps because it has to be recited at the foot of the altar before one can go up to it. When one understands the underlying liturgical logic here relative to the altar viewed as the “ara crucis” [“altar of the Cross”], a place sacred and terrible, where the redemptive Passion of Christ is made present, a prayer expressing the unworthiness of anyone to ascend those steps makes sense. The disappearance of Psalm 42 (which in the following years would be eliminated from every Mass) seems, instead, to be a wish for a preparation ritual having to do with an altar that is, symbolically, a common table rather than Calvary. As a consequence, the holy fear and sense of unworthiness affirmed by the psalm are no longer inculcated.

(MR 1952): Mass begins with the prayers at the foot of the altar, Psalm 42 (“Judica me, Deus”), and the Confiteor.

12. (OHS 1956): In the same decree, all the rites of the Vigil of Pentecost are abolished, except the Mass.

Commentary: This hasty abolition has all the marks of being tacked on at the last moment. Pentecost always had a vigil similar in its ceremonies to that of Easter. The reform, however, was not able to deal with Pentecost. But then again, the reformers could not leave untouched two rites which, fifty days apart, would have been, in the one case, a reformed version and, in the other, a traditional version. In their haste they decided to suppress the one they did not have time to reform; the ax fell on the Vigil of Pentecost. Such improvident haste resulted in rapid editing of the rites of the Vigil of Pentecost, so that the texts of the Mass which traditionally followed those rites no longer harmonized with them. Consequently, in the rite thus violently mutilated phrases remain which are rendered incongruous with the words of the celebrant during the Canon. The Canon presumes that the Mass is preceded by the rites of Baptism, which have been, however, suppressed. As a result, thanks to this reform, the celebrant recites during the special “Hanc igitur” words related to the sacrament of Baptism during the Vigil, whether the blessing of the font or the conferral of the Sacrament: “Pro his quoque, quos regenerare dignatus es ex aqua et Spiritu Sancto, tribuens eis remissionem peccatorum” [“For these, too, whom Thou hast deigned to regenerate with water and the Holy Spirit, granting them remission of their sins”]. (136) But there is not a trace of this rite anymore. The Commission, in its haste to suppress, perhaps did not notice.

(MR 1952): The Vigil of Pentecost has rites which are baptismal in character, of which the “Hanc igitur” of the Mass makes mention.

GOOD FRIDAY Changes